The Peruvian Congress’s ousting of President Pedro Castillo on Dec. 7 led to two weeks of protest throughout the country, with at least 50 reported dead in clashes with law enforcement. The appointed successor, former Vice President Dina Boluarte, announced for advanced elections in April 2024, but vehement Castillo supporters call for her resignation and the dissolution of Congress, which they view as corrupt.

In late January, police in Lima used tear gas to disperse crowds when thousands of protestors, most from rural and indigenous communities, converged on the capital. They represented pro-Castillo areas in the southern part of the country, near the Bolivian border, where most of the violent protests have occurred.

In Arequipa, Peru’s second largest city located 400 kilometers from the southern border, AAPG members Luis Alexander Alvarez and Alexandra Del Castillo took refuge in their homes.

Alvarez, a mining and hydrocarbon geologist, said the social unrest directly affected him and his family.

“The protests against the corruption of the constitutional Congress are very violent and generate instability in my area,” Alvarez said. “We could not go work because crowds could attack us.”

Alexandra Del Castillo, an intern currently working on exploration potential and reserves estimation projects at national hydrocarbon agency Perupetro, also stayed in Arequipa when protests and attacks kept her from traveling to work in Lima.

Del Castillo noted that political instability started long before Castillo’s ouster in December.

“In recent years, Peru has been going through a political crisis that increased with the passage of time. We face political instability, with several presidents in a short time, each one moving away from the good of the country. This crisis is affecting the labor market because companies that come to invest in Peru see our political crisis and no longer consider the country to be a good option for them,” she explained.

Alvarez agreed, adding that the situation continues to deteriorate for geologists living in the country.

“Unfortunately, Peru has suffered a political crisis for a long time: political disorder, bad decisions and interests of the authorities make the political environment a chaos,” he said, noting the instability this creates for investment in resource exploration projects.

“The situation for geologists is not very favorable. There is a disordered flow of activities, unemployment, protests in areas with mining or oil reserves. The socioeconomic environment is very complicated for all professionals and for society,” he added.

Alvarez noted, however, that despite the country’s challenges, Peru provides rich opportunities for geologists.

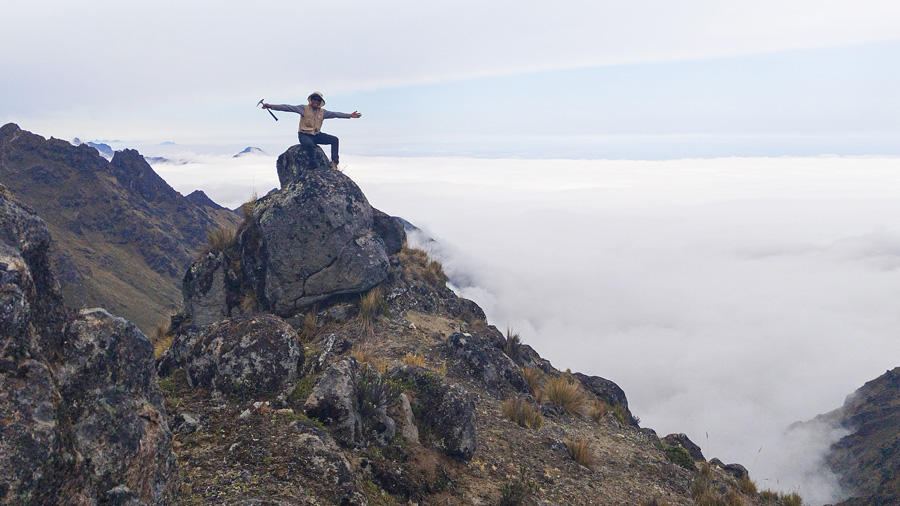

“The Peruvian Andes are wonderful, and there is a lot of geology to discover and rediscover. Its tectonic and structural complexity make it wonderful. Peru for me is a geological laboratory par excellence,” he said.

The country’s natural resources provide new fields for geologists interested in moving beyond traditional petroleum exploration and development, Alvarez noted.

“Geotechnics currently offers many opportunities,” he said. “Mining is next because Peru is a mining country, especially in the south, which is classified as a copper, molybdenum, gold area. Also, economic geology is a highly paid branch in Peru.”

The Role of AAPG

Alvarez, a former Imperial Barrel Award competitor and AAPG student member, said the Association can help prepare students to work in a variety of geological fields.

“When I was a student, AAPG provided a basic knowledge of geology, and representing the university in the IBA helped me gain valuable experience in the exploration and evaluation of oil data,” he said.

“Opportunities for growth and memberships sponsored by large companies, are great incentives for students to be part of the AAPG.”

Involvement with AAPG motivates students like Juan Manuel Rojas, current AAPG student chapter president at the National University of Engineering in Lima.

“Personally, Peru’s situation has closed some doors for me to be able to get an internship, but in the end it encourages me to keep going even if it is more difficult,” he said.

Rojas said his love of the countryside, nature and travel inspired him to study geology. After graduation, he hopes to get a job that enables him to grow professionally and continue learning about the field he loves.

In the meantime, he focuses on his coursework, goes on field trips and remains active with AAPG, an organization he credits with giving him direct access to senior professionals.

“The greatest opportunities we have are the engineers who teach us at the university, who guide and advise in order to have a better development and do better in the company where we will apply to work,” he said.

Rojas’s colleague Jesús Aguirre, ninth semester geological engineering student and vice present of their AAPG student chapter, said finding work is easier said than done.

“The situation for geologists is complex,” he said, “Recent events in the country affect job searches for students in their final semesters, students like me.”

Aguirre said that in addition to a lack of internships and job opportunities, geoscience students also face economic stressors related to price increases.

While waiting for the situation to improve, Aguirre focuses on his role with AAPG.

“As vice president of the chapter, I’m in charge of promoting the chapter, disseminating information about hydrocarbons and helping more people know about what we do,” he said.

Aguirre said AAPG chapters in Peru and beyond provide the opportunity for students to learn more about geology and find a career path.

“We can share information about different branches of geology, so students can explore and choose the one they like best,” he said.

Del Castillo, the Perupetro intern who also serves as president of Peru’s AAPG Young Professionals Chapter, said she hopes the Association can help her colleagues to find opportunities in crisis.

“Our challenge now is to move forward and help our industry find the best path,” she said. “AAPG can help us continue to strengthen our knowledge and inform us about job opportunities. The best things about being a part the AAPG are the learning opportunities it offers you, the knowledge it gives you, and the opportunities it provides for professional development.”

The Role of Professional Associations

Vidal Huamán, Cusco native and general manager of VIES Geoscience Consultants, confirmed the role of professional associations in promoting career and personal development for current and future energy industry leaders.

Huamán serves as president of the Geological Society of Peru (SGP), one of the region’s oldest geological societies, founded in 1924. He noted that, in addition to being a historic reference for geology in Peru, SGP also develops projects to generate opportunities for geoscientists, primarily through disseminating information about geology and its contribution to the country’s development.

In 2021, SGP launched the Forum for the Promotion of Investment in Mining Projects, developed jointly with the biannual Peruvian Geology Congress. The Society also runs the “Explora Peru” training program, a six-month professional development initiative for young professionals and students enrolled in final semesters at 11 Peruvian universities.

“Explora Peru serves to reinforce young geoscientists’ knowledge, to promote their professional growth with a high level of preparation to face new challenges, and to give visibility to new talents,” he said. “Additionally, the SGP works on the permanent dissemination of scientific and technological advances and current issues related to Earth sciences.”

Difficult Times for Peru

Huamán said Peru’s recent political history creates challenges far beyond the hydrocarbon sector.

“In the last five years we have experienced difficult times of political instability, having up to six presidents during this period, which definitely generates mistrust in private investment and has had a negative impact on the economic growth of the country,” he said.

“Truncating the development of projects of great importance has generated more poverty and a social inequality,” he said. “The population has lost hope in its political class, because many governments have broken their promises and forgotten many regions, even those where we have significant mining and hydrocarbon activity.”

Huamán said Peru’s hydrocarbon sector, and the country as a whole, will continue to suffer if longstanding social and economic struggles remain unresolved.

“The current government must act immediately to enact policies that meet society’s demands and seek social peace. The support of institutions, professional associations and organizations is essential to getting us out of this crisis.”

Effects on Geologists

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent global downturn compounded the already challenging situation faced in the country, he said.

“Geologists were affected by the country’s political situation, the pandemic and opposition from some communities to mining and oil activity, which ended and paralyzed several projects. All this affected the employability (and) professional development of geologists. The situation is even more serious for the hydrocarbons sector, due to the oil crisis and the energy transition,” he said.

“Approximately 70 percent of the geologists in Peru dedicated to this sector lost their jobs, and to this date have not been able to get back into the workforce. There is a lack of investment in hydrocarbon exploration, despite the fact that Peru has great potential to explore, and this is due to the lack of state policies to encourage, promote and reactivate the oil and gas sector.”

Huamán noted that, faced with long term challenges in oil and gas careers, many of his colleagues have decided to make a change.

“It should be noted, the vast majority of oil geologists have a long and recognized career, and many are choosing to migrate to other activities such as mining, geotechnics, environment, hydrogeology, among others,” he said.

A Personal Pivot

Huamán has experienced migration himself, moving from a career in petroleum geology and geophysics to work with renewable energies.

“Peru’s political instability, the paralysis of the hydrocarbon sector, and the energy transition affected me personally and forced me to reorient my goals and objectives,” he said. “I chose to migrate to another sector related to the search for strategic minerals, including lithium and rare Earth elements, as well as the search for clean and renewable energies such as geothermal energy.”

He provides services to companies interested in investing in the search for new resources and describes the process as a new personal challenge.

Exploring Opportunities

Huamán said, like him, geoscientists in Peru have options in both traditional and emerging fields.

“Peru, by tradition, is a mining country, and mining is the engine of the Peruvian economy. The vast majority of geologists practice their profession in the mining sector in different technical areas of exploration and production, as well as support areas like geotechnics, hydrogeology, environmental, geometallurgy, etc.,” he said.

“We live in an increasingly dynamic and changing world, with a demand for new resources that are still little studied and explored,” he said. “Additionally, automation processes reduce the employability of professionals, including geologists. Geologists must be increasingly creative, have the ability to reinvent themselves and think outside the ordinary, leaving some paradigms behind, and assuming challenges that await us for the search for new resources in increasingly complex areas.”

Huamán also noted that geoscientists’ responsibility extends beyond the office, or the field.

“Geologists as generators of projects, primarily in the mining and oil sectors, must also assume the role of communicators of our work to society. Because there continues to be so much ignorance about our profession and its contribution to society, it is important to create spaces to reach the general population and also create expectations in students who wish to pursue this career,” he said.

“Another important aspect is our approach to the population, particularly to rural and native communities, where the state has not yet been able to articulate the importance of mining or oil projects, essential resources for the socioeconomic development of the country. A lack of knowledge and dissemination them to reject certain projects,” he said.

Huamán recounted a recent experience in the Puno Region, Southern Peru, where he traveled twice to lead a work team to inspect areas of interest and collect geological samples.

“I went with some trepidation, since I heard from other geologists that the peasant communities in the areas were radically opposed to mining activity in this area,” he said.

Huamán’s team brought in final semester students and recent graduates from the University of the Altiplano Puno, located in the region, and they hired support local personnel from the area to assist with project development.

“I was surprised that, after carrying out the two campaigns, we did not have any type of opposition. Our team members were able to co-exist with the local communities, without any distinction. We explained our daily work to the local team, who learned and enjoyed what we did, and we shared everything equally, making them feel that we were all one team. On the last day of the project, we said goodbye with great sadness, but also with hope and optimism that we would meet again.”

Huamán said transparency and mutual understanding are very important for achieving trust, which allows dialogue and the exchange of ideas.

“It is important for communities to understand that mining and oil activity will generate opportunities for development and growth for all and that they are a part of the process. Fair and equitable treatment means a lot to them. No one can feel superior to the other, but there must be an atmosphere of respect.”